I am interested in the roles of microbes in allowing hosts to adapt to environmental changes. Scientists have observed microbes (bacteria, fungi, and viruses) making a difference in coral reef bleaching (Webster & Reusch, 2017), drought tolerance in plants (Márquez et al., 2007), and fighting invasive species. Understanding how microbes shape the boundaries of what environments their hosts can inhabit will become even more important as the conditions of Earth shift due to human influence. For the past ten years (for details on past work, click here), I have mostly been focusing on microbes that associate with insects (i.e., insect-microbe symbioses). Insects are amazing for studying host-microbe associations since they occupy almost every imaginable environment, their microbiota is generally less diverse than mammals (Douglas, 2011), and you can maintain them in a small amount of laboratory space.

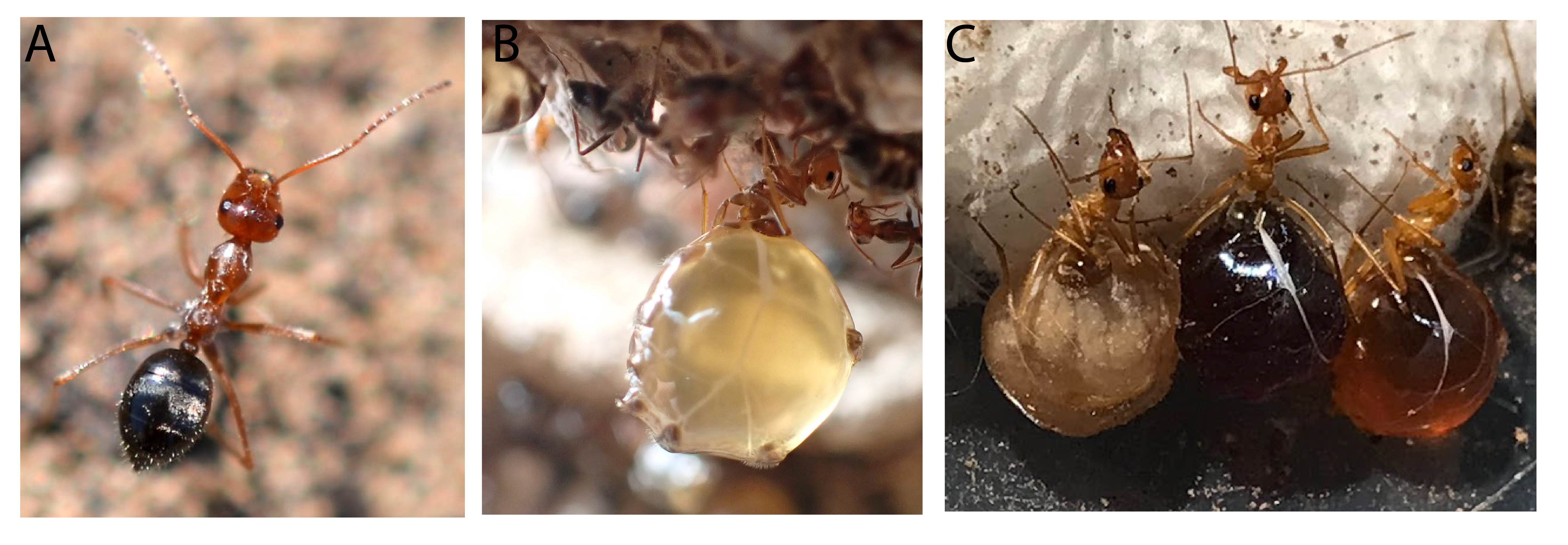

Ants offer a fascinating platform to explore how microbes are involved in the evolutionary trajectories of their macroscopic hosts. The ~13,000 known species of ants fill a variety of niches worldwide and I’m interested in exploring the composition and role of microbes in impacting the diverse approaches to survival amongst ants. I am currently focusing on a group of ants that have convergently evolved distinctive food storage behaviors, the honeypot ants. This group of ants is comprised of at least sixteen independently evolved genera located in the arid regions of North America, Africa, and Australia. In all lineages, honeypot ant foragers collect resources (e.g., nectar, honeydew, insect carcasses), and then provide the nutrients to specialized worker ants, called repletes. The repletes store the fluid in their swollen guts, and during times of scarcity, they supply the colony with the stored fluids. The fluid is specifically located in a subdivision of the ants’ foregut called the crop, which can expand with large amounts of food, sometimes up to the size of a marble!

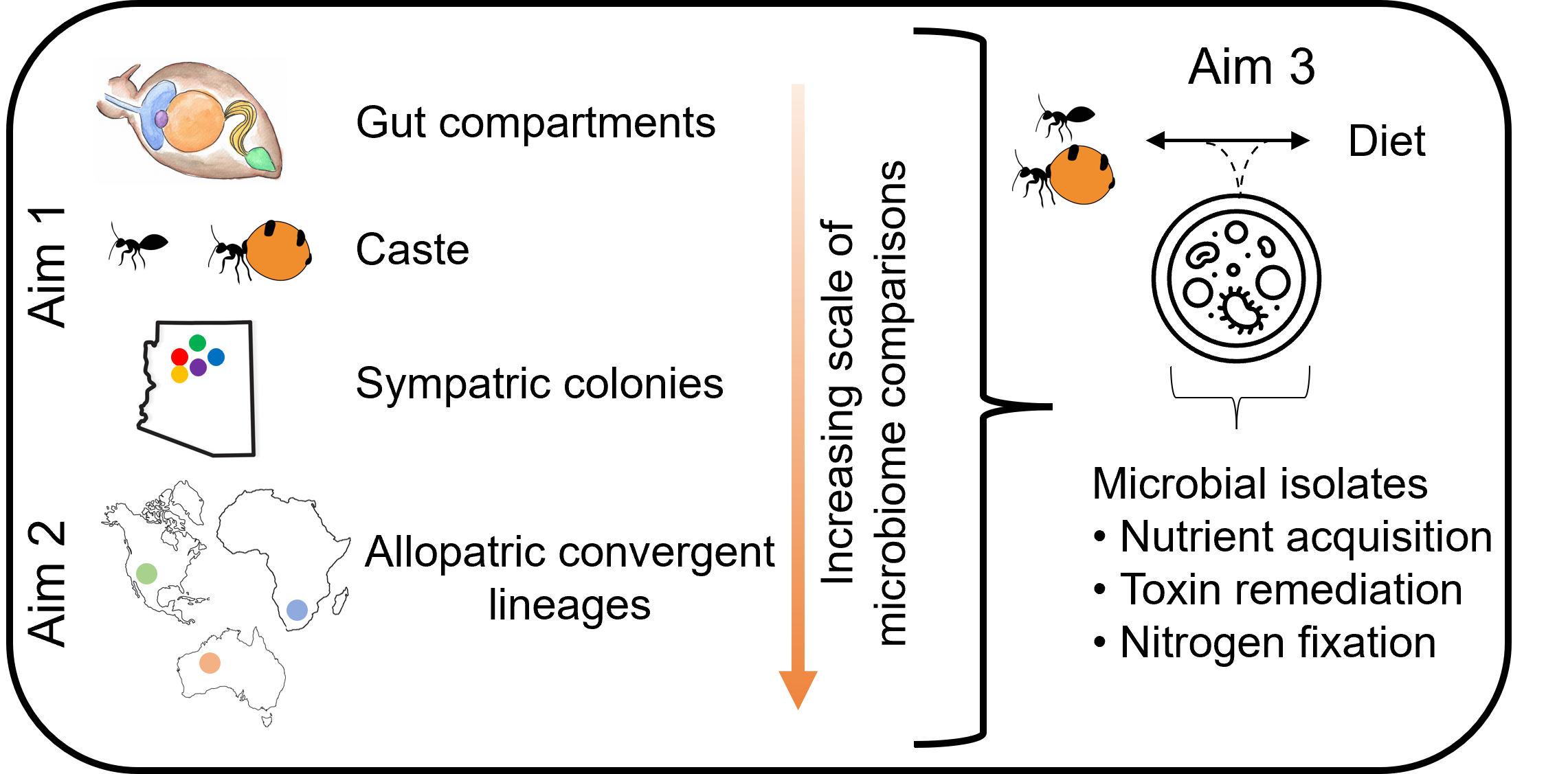

Despite the eye-catching nature of honeypot ants, very little is known about their biology and ecology, and even less so about their associated microbial communities. Overall, the objective of my work is to characterize the microbiome of honeypot ants across multiple scales to examine whether convergently-evoved insect hosts harbor convergent microbiomes, and to describe the potential functions of the microbiome for host fitness in this unique system. To begin our understanding, I am focusing on North American honeypot ants in the genus Myrmecocystus to characterize the microbial communities between different digestive organs, castes, colonies, and species.

Summary of the overall aims of the Khadempour Lab’s honeypot ant microbiome work. I am largely focusing on investigating the microbiome of Myrmecocystus honeypot ants, comparing the taxonomic composition via amplicon sequencing at multiple scales (Aim 1) and assessing the role of the microbiome in mediating their diet (Aim 3).

Works Cited

Douglas, A. E. (2011). Lessons from studying insect symbioses. Cell Host and Microbe, 10(4), 359–367. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chom.2011.09.001

Márquez, L.M., Redman, R.S., Rodriguez, R.J., & Roossinck, M.J. (2007). A virus in a fungus in a plant: Three-way symbiosis required for thermal tolerance. Science 315:513-515.

Webster, N.S., & Reusch, T. BH. (2017). Microbial contributions to the persistence of coral reefs. The ISME Journal, 11, 2167-2174.